It’s been a minute since I’ve written anything substantial here. I didn’t see much point in posting anything long while everyone’s attention was focused on elections. Meanwhile I’ve been chewing on how unmanned, autonomous systems employed at scale change the game for electronic warfare. I’ve been meeting with force planning and technology experts and receiving first hand reports about how things went down in the recent Kursk offensive by Ukraine into Russia.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that new tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) are emerging as UAS become the workhorses of modern combat. The introduction of the drone in the 21st century has become as impactful as the missile was in the last 50 years of the 20th. While today’s drones (like the one’s shown in Ukraine below) are primarily remotely piloted, it’s only a matter of time before they go partially or fully autonomous.

Going forward, drones will comprise not just the vanguard of combat forces but many of it’s other elements in sensing, logistics and strike. This makes the wireless spectrum - and the communications networks that leverage it- a more vital domain of combat than ever. While the kills above are almost entirely taking place with remotely piloted First Person View (FPV) drones, it doesn’t take much imagination to see drone combat growing to the intelligent swarm scale portrayed in science fiction:

In this piece I will talk about how we got here, the current challenges in electronic warfare and how our doctrine and EW systems are not equipped to solve them. I will introduce how we will solve it: by tactically shifting from an emphasis on suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) to suppression of enemy emitters and networks (SEEN).

Networked drones and implications for EW

“Our culture tends to fill our heads with all kinds of false notions, making us believe things about what the world and human nature should be like, rather than what they are actually like.” - Robert Greene

It is an age old adage of warfare that “the enemy gets a vote”. Unfortunately the US defense industrial complex is often guilty of building sandcastles in the sky and trying to develop the solution for the war they want to fight rather than creating optionality and acquisition agility that allows them to adapt to the war they will fight.

There is few areas where this is more apparent then in the domain of electronic warfare. Here, in spite years of lobbying by the Association of Old Crows (AOC) and several former Electronic Warfare Officers (EWO) such as Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) serving in congress, we are still largely leveraging an EW enterprise organized around cold war legacy platforms designed for intelligence preparation for the battlefield (IPB), self-protect of aerial and ship assets, and a mission set that hasn’t evolved much from the cold war. As Table 1 illustrates, despite a 15 year effort to recapitalize our electronic warfare assets, we are still very much wedded to exquisite systems, albeit on newer platforms.

It should be noted that this isn’t all the Pentagon’s fault: the peace dividend of the ‘90s ended a lot of programs and during the last two decades Congress has only passed an actual defense budget on time in only 5 of the last 20 years. This has left acquisition officials with little choice but to cobble together incremental improvements to existing systems rather than build new ones. That being said, the Pentagon is infamous for fetishizing swiss army knife systems that are exquisitely designed and the EW domain is no different.

“In the year 2054, the entire defense budget will purchase just one aircraft. This aircraft will have to be shared by the Air Force and Navy 3-1/2 days each per week except for leap year, when it will be made available to the Marines for the extra day.” - Augustine’s 16th law (Norm Augustine was the last CEO of Martin Marietta Aircraft)

Where new systems have been developed and deployed successfully, they are mostly as point solutions like countering Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) during the GWOT campaign or more recently for drone detection and defeat systems (C-UAS). One counter example of this was the ALQ-249 stand off jamming pod which was recently deployed on Navy Growler jets in the middle east, after nearly 15 years of development (I was a system engineer on this program early in my career). While it certainly represents a huge step up in capability, a pair of $15M pods mounted on a $70M aircraft is still an exquisite system that is only available in limited numbers and has range limited by the carriers it flies from.

Meanwhile, the battlespace, following our every day lives has become increasingly crowded with emitters - sensors and wireless systems, along with the robots they control, have become ubiquitous. The spectrum has become as vital to 21st century warfare as the shipping lanes were to the 20th.

“In modern warfare, electromagnetic warfare may be the main effort to achieve the desired strategic effects.” - Gen Charles Q. Brown, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

We are flying into a hornets nest

The US collectively spends over $5B a year on electronic warfare systems with that spending expected to go up at least 50% by the end of the decade. But as the previous section showed, these capabilities are limited mostly to self-protect systems on things like fighter jets or mostly locked up in platforms that are too expensive to really be usable in anything but a full scale conflict.

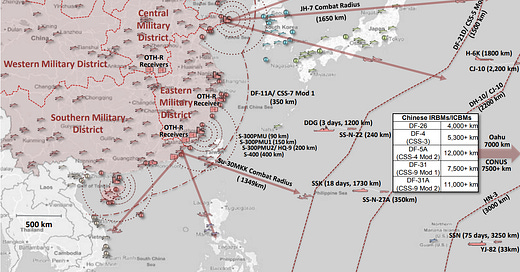

In a full scale conflict, as we are seeing daily in Ukraine and as Figure 2 shows, Chinese air defenses are going to push our flywheel systems out many hundreds of kilometers from where the fight is at and even the Growlers would have their hands full dealing with the inner rings of SAMs and their targeting and early warning radars.

Worse yet, studies show that it may take 40 or more weapons (delivered by $100M-$1B platforms) to penetrate this web of defensive systems to hit a single target - making our precision strike doctrine entirely too costly. This is the offensive corollary to what we have been seeing in the Iran-Israel conflict and Houthi cruise missile campaign in the Red Sea: where thousands of multi-million dollar missiles are necessary to protect against $30,000 drones and $150,000 ballistic missiles.

In the absence of definitive air superiority, it’s doubtful our exquisite systems would fair much better than the Russian A-50 Mainstay surveillance planes the Ukrainians have been making Mince meat out of in Ukraine to the tune of $350M a piece. Yet these are the same systems we would need to rely upon to understand defeat and target enemy communications systems that are responsible for managing the complex web of autonomous systems at play on the modern battlefield.

Our enemies are investing in drone technology heavily. The Russians are claiming they will build over a million drones this year. The Chinese build over 20,000 a day ( over seven million/year). Meanwhile US domestic production is stubbornly stuck at 20,000 annually (though increasing) and many of our suppliers are still dependent on Chinese supply chains for critical components like batteries, motors and motor controllers. Chinese sanctions recently kneecapped leading US drone supplier Skydio in fact by cutting off batteries in retaliation for selling to Taiwan.

Everywhere we look, asymmetric enemies pervade who will bleed our magazine of expensive precision missiles dry and beat us with cheap stuff that they can produce at rates two orders of magnitude faster than we can. The consequences of hollowing out our industrial base for decades in the name of “efficiency” while our military contractors focused on precise exquisite systems is laid bare. Worse yet, this is just the beginning, as we are still fortunate enough to be dealing with 1 v 1 systems and not yet autonomous swarms.

The scale of drone warfare changes the game

“Quantity has a quality all of it’s own”- Josef Stalin

With the kind of multi-layered defenses shown in Figure 2 in place, our doctrine of establishing air superiority to ensure freedom of maneuverability on the ground is called into question. As the Ukraine war has shown in volumes, we must develop the ability to fight up close and in the low altitude environment known as the air littorals (shown in Figure 3), in spite of lack of air superiority. This is the space dominated by drones and autonomous systems which we expect to be deployed by us and against us at scale. Just to cite one statistic from the NATO conference I attended in Krakow in June: 30% of the vehicle kills achieved by the Ukrainians conflict were due to kamikaze drones. Some may attribute this to the fact that neither side has achieved air superiority, but it’s hard to imagine looking at Figure 2 that air superiority is something we should expect at the onset of any future conflict.

The density of drones in the air littorals that we’ve seen in Ukraine has reached a dizzying level: as many as 800 per square mile. Add to this the ubiquity of cell phones, IoT, Push To Talk radios, radars, jammers and other emitters in the space and you have a signal environment that is impossible to sort out from the 200km+ range away that our SIGINT systems will find themselves at.

The shear emitter density of the modern battlefield will drive SIGINT systems to the tactical edge - it’s just geometry.

Just as a thought exercise, consider a DF system with pristine resolution of .5 degrees at low frequencies (800 MHz, 600 MHz or 2.4 GHz) where a drone and drone controllers datalinks emit. At 200 km range, you could have as many as 8000 drones in each angle bin under peak conditions - impossible to sort out and separate from stand off distances. You need sensors up close in large enough numbers to find, fix and finish these systems before they overwhelm and finish you.

Move over Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD)

What was in the past a “suppression of enemy air defenses” or SEAD problem, with sensing, electronic attack and HARM missile attacks principally focused on a few radars and air defense network comm systems to clear the route for the strike package, has turned into a suppression of enemy emitters and networks problem as we now face a quagmire of networked comms, drones, cell phones, radios and jammers on the modern battle field.

The economics of taking out a $100M SAM missile battery like a SA-300 system are completely different than taking out a $15,000 GPS jammer or a $1,500 drone controller. Using a $1.3M AARGM-ER missile to take out a $100M missile battery is a great trade. A $15,000 jammer? Not so much.

How we change the game

The solution to this is that the drones and weapons systems on the tactical edge must themselves become the SIGINT systems. Moving sensors to cheaper drone platforms that are more expendable enables them to get closer to the enemy without fear of putting a soldier’s life at risk. At close ranges, precise geolocation and passive tracking of moving targets becomes more feasible with cheaper systems- signals separate better geometrically at closer ranges, making them easier to fix and track.

Closer range also means less sensitivity is required to detect the signals and a lower overall density of emitters is within line of sight. Cheaper, more expendable systems can be employed here as opposed to highly sensitive ones. More emphasis must be placed on communication intelligence (COMINT) rather than radar intercept (known as ELINT) and analysis at or near the tactical edge. These are systems that we currently don’t field in large quantities but lessons learned from Ukraine are making them even more vital.

“COMINT has very much moved from that preserve of the few into something hugely necessary for the masses…I think what we’re seeing now, is how do western forces break out of the mindset of the few and actually have a capability that has mass?…There’s a lot of western solutions that became too exquisite, too high value, too low quantity. Whereas now we’ve seen something…driven by the fact that you’ve got 1000s of assets up and down the front” - Graeme Forsyth, SPX Communication Technologies (from Journal of Electromagnetic Dominance)

So perhaps it’s time for new terminology and a new mission focus? We are no longer talking purely about suppression and destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) as a mission; we are talking about suppression and destruction of enemy emitters and networks (SEEN/DEEN).

The SEEN/DEEN mission will require new systems that are cheaper, more ubiquitous and more expendable. We have the capacity to build them (and not to talk my own book) but it is a key focus for us at CX2.

In a future post, I will get into the military organization of drone armies and how we are starting to see the emergence of large scale tactics and strategy, moving beyond mere 1v1 drone vs target melees, but for now I close with emphasizing that a new mission set brings with it the need for an entirely new set of systems built around it.

We are slowly getting the message…slowly.

Some members of our military industrial complex would prefer to bury their heads in the sand and continue to build more F-35s, NGAD and other systems. These air superiority systems will do us little good if the enemyis able to flood the zone with thousands of autonomous systems who pin down our ground forces with strikes and soak up our expensive precision guided munitions that have allowed us to win the last major force operations and which we are currently reliant upon to take out these systems with. Hopefully efforts like Replicator and efforts by defense innovators to change the way we fight will win out here. We can’t continue to fight the war we want to fight, we have to prepare for the war we will fight.

So much valuable info in here. Appreciate the post

How do we get these systems with significant commercial crossover? Tariff Chinese drones out of the market? Government funding for municipal drone shows? Dual use is critical for obtaining mass at the speed required.