How to realistically estimate market size and revenue in defense start ups

How do you best estimate the market size for a defense startup and evaluate their revenue plan?

Motivation

I was at a dinner a couple weeks ago with a group of investors, executives and start up founders in the aerospace & defense space and someone asked a very good question: “how do I make an independent assessment of the TAM (total available market) for a particular defense start up?”

This question is coming up a lot more now as we see more and more investors looking at the aerospace & defense space.

The A&D sector is a hard nut to crack for investors. First, the DoD is a massive $800B/yr labyrinth with very hard to understand rules for how monies are budgeted and moved around throughout the year to support various acquisition initiatives. Second, the customer life cycle in this space is very long: some engineers in traditional aerospace can spend their entire careers working in a single defense program and they can take 10+ years to go from drawing board to program of record. Third, headlines often focus on total potential contract value (“Acme.ai awarded IDIQ from DARPA for $10 billion!”) without looking at the actual details of the contract like funds allocated by year and Period of Performance.

So I thought it might be helpful to share some of my experiences and rules of thumbs that I use as a former defense start up CEO, former big aerospace proposal manager and strategic analyst, as well as an investor (I have personally in 3 defense companies in the past 3 yrs as well as indirectly in several others as an LP) and advisor to funds and companies doing diligence in this space. Hopefully this will be helpful for a few folks just wading in.

For this piece, I’m going to focus on the TAM/SAM/SOM piece and some of the nuances of the contract types. In a future blog post I’ll get into the acquisition process and the road to Programs of Record but for the sake of brevity, let’s focus on the first piece. I’m also not going to cover how to do this for the commercial dual-use market piece as I assume that is covered by others elsewhere.

Some definitions for the non-BD person

Here’s a graphic I stole from Hubspot that succinctly shows TAM, SAM and SOM and how they relate to each other:

Why most TAM estimates for defense out there are terrible

One of the biggest challenge in the door for market sizing in defense is all the noise generated by clickbait reports. These are meant to sell ads or reports on Google than actually stand on their own as real parsable analysis.

A cottage industry of analysts is out there producing garbage analysis about market sizes with names like “Mordor research” and “Grand View Research” that are really just trying to sell you a report for thousands of dollars that they had a group of analysts (usually in India or some where else with cheap white collar labor costs) scouring the internet to create. You can literally find these on just about any sector and they are the coin of the realm for bad TAM estimates. I suspect it won’t be long before we see generative AI generating these reports rather than analysts and then they will be move from useless to hallucinatory.

These reports usually have TAM numbers that are fairly bunched together in the present and then diverge by as much as an order of magnitude or more in the future. Here’s an example from the counter UAS space using some sources from a quick Google search (note to Substack- why can’t I just generate a table in your tool rather than having to post it as a picture?). I’ve highlighted the highest in green and the lowest in red to highlight the issue.

In terms of answering the question “what will the market be five years from now?” These sources are absolute garbage in/garbage out and can easily be cherry picked to get the highest CAGR and TAM possible for justifying obscene valuations. I haven’t bothered to check their math but I suspect that the CAGR numbers don’t even support the growth in the starting and ending numbers.

The other thing to understand is that the TAM net is likely cast too wide here for a particular product. In the CUAS space there are over 500 products currently being marketed as of 2019 (see table below from the Bard College report), so you have to be a little more specific than just Counter-UAS:

Note that for this market in particular, incumbent systems like RADA Radars from DRS/Israel, The TPG-50 radar from SRC, X-MADIS and others already are bought and in procurement and not likely to be displaced, because defense contracts tend to be really sticky. That’s also just the radar segment - if you read the Bard report, you’ll see there are dozens of modalities of detection alone, not to mention the rest of the kill chain that is pulling money from the same pot.

So the Service Addressable Market is what really matters here. You need to identify where your product can actually play in that market that someone else already hasn’t claimed.

Moving from TAM to SAM to SOM - Bottoms Up rather than Top Down

The key takeaway from the last section is that most future TAM estimates you can find that are publicly available are awful and tend to be down revised later. Also, their estimates vary wildly on how big the market will be five or more years from now when you are actually scaling a product into market and these envelopes matter.

So if the TAM estimates we get out of these reports are useless, where does that leave us? I honestly think a better approach is to go “bottoms up” rather than “top down”.

Top down numbers from boiler room research firms, that know little about defense, with minimum visibility to their assumptions often make little sense. Best to start by estimating how many units of your product can be sold and then back into pricing to determine your market size.

Start by trying to quantify the total number of available customers or defense programs where your product may be applicable. “How many vehicles can I hang this radar off of?”// “How many surveillance towers per base”// “How many individual users are there for this intelligence software?”, etc. At least then, there is a set of assumptions you control and you can defend (rather than citing a $4500 clickbait report).

Rough Order of Magnitude Costs

Next, try and determine the average unit cost (AUC) for your product. If it’s very early in your development cycle and you don’t have precise Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) yet, you can probably estimate it with a Rough Order of Magnitude (ROM) estimate. The key here is to get within +/- 25% of where you think costs will eventually land, not +/- 1%. You can even throw a “ROM factor” on it, if you are truly concerned about pricing, which you can take out later as you get more certainty about the design baseline. The easiest way to come up with an answer is by adding together how much non-recurring engineering cost you think you will have amortized over how many units you think you’ll sell in the first 5 years of production (don’t try to do lifetime exercises, it’s too hard), your estimated BOM cost per unit and recurring engineering costs per unit.

So bottom line, rather than relying on someone else’s number they seemingly pulled out of thin air (as far as you know, since you have no visibility into their assumptions), you can basically bypass that useless number and instead take a decent guess based on your own numbers from the bottoms up. This will yield an answer closer to a Service Addressable Market (SAM), or perhaps even the Service Obtainable Market (SOM), if you go a little deeper.

Customer Furnished Top Down: the Presidential Budget Justification Books and checking your bottoms up

The Pentagon is very transparent about how much stuff it wants to buy every year. This can give you an excellent top down parity check against the bottoms up exercise you just did.

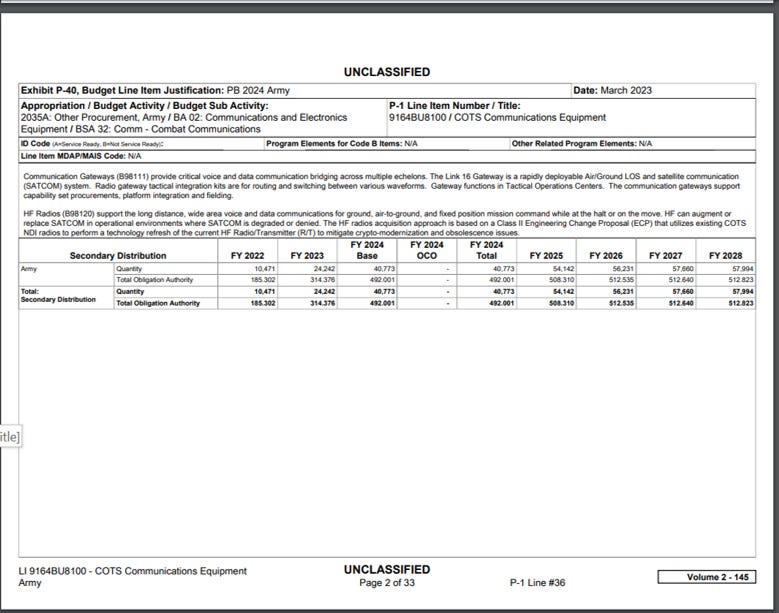

Each year, the DoD releases detailed asks to Congress on a line item by line item basis along with the “why” in the Justification Books as part of the presidential budget request. Here’s a link to this year’s Justification Book for the Army. It’s helpful for both identifying the Service Addressable Markets and the amount budgeted to specific programs (basically your SOMs). Here’s an example page of interest below:

I think it’s important to think of each of the services, along with select international customers, as individual SAMs. This is because while they aim for commonality at the huge program level (think programs like Joint Strike Fighter, JEDI and AMRAAM), for smaller efforts they usually have totally different CONOPs and requirements. The differences are sometimes so large that they don’t even use the same vocabulary to describe the same basic things (e.g. an electronics box that is field replaceable for the Air Force is called a Line Replaceable Unit or LRU; the Navy calls them Weapons Replaceable Assemblies or WRAs).

The services have different procurement offices, roadmaps (Program Objective Memorandum of POMs) and different priorities. At the big primes, its not uncommon for business development people and engineers to spend their whole career working with one customer. Occasionally you’ll see Joint Program Offices (JPOs) for programs that get used by multiple services but the vast majority of the time, expect each service to have their own spin on things.

The budget line items in the Justification book have a lot of detail that can be helpful in determining what lines of effort comprise the service obtainable markets, how those change over time, potential competition and even cost. Below is the program line item for COTS communications equipment where there is a fair amount of venture investment going on right now:

There is some incredibly useful information here in terms of how many radios of what types they are looking to buy and existing systems they are replacing. The government is literally giving you an outline of what the potential SOM looks like here.

International customers should also be treated as their own individual SAMs because they will require individual export approval (the joys of ITAR) and may require a variant with differences in performance. My suggestion is that unless you have a specific mature international customer you are looking to sell to, focus on domestic first. The international is not likely to be as large as domestic until you jump through all the export wickets and those can take years.

Distinguishing between SBIRs, OTAs, IDIQs and Programs of Record (PoRs)

Now that we have gone over the bottoms up methodology, it’s important to explain the different types of contracts and how they work. In the defense space, contracts come in many acronym laden flavors and are often just Customer Funded R&D Dollars (CRAD) and don’t represent actual product revenue (the maximum fee on CRAD contracts is usually 15% or less- “Cost Plus”). You’ve probably heard discussions about the “DoD acquisition valley of death”, which is simply defined as R&D projects that fail to transition to Programs of Record (PoR).

The holy grail of defense products almost always comes from selling products into the Programs of Record (PoRs), which you saw in the justification book. PoRs are almost always multi-year and sometimes multi-decade contracts approved by Congress which once you win, you’re in, unless you really screw it up. So predictable and dependable is the income and earnings from PoRs that many on wall street analysts effectively treat large defense contractors as “annuities” because their income is so predictable when spread over a diversified set of mature PoRs.

Understand that of about 50,000 contractors for the DoD, about a dozen are actively managing the 88 Major Development Acquisition Programs or MDAPs (>$3B for procurement, >$525M for RDT&E) at any given time. Of the >$400B spent on defense each year, 47% goes to the top 25 contractors, many of which are pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer (#4), so breaking prime contract awards are still, despite years of “innovation theater” very much a power law phenomena. That being said, subcontracts can also be a lucrative way to break in and many contractors like RTX (formerly Raytheon Technologies), BAE, Honeywell and Pratt & Whitney manage to make a ton of money this way too.

Its important to understand what is product revenue (usually from a PoR) and what is just CRAD that can helps mature technology that could prospectively transition to a PoR at some point in the future.

The classic mistake made investing in this space is misinterpreting CRAD funding for product revenue. CRAD is awarded in a variety of vehicles like SBIRs, STTRs, OTAs, IDIQs (various contract vehicles I won’t cover here) which are great early indicators of interest for the big contracts that come with Programs of Record. However, they are rarely PoRs themselves. PoRs are almost always defined by a line item in the DoD budget approved by Congress.

SBIR contracts are limited to about $750k-$1.5M with rare exceptions. In credit to the government, we are starting to see more SBIR Phase IIIs - this is actually a misnomer as it’s actually funding from outside the program but attached to the same contract number- that can be as much as $9.9M (this is usually done using something called a Military Interdepartmental Purchase Request (MIPR)). That’s about the max that can be appropriated without Congress having a say and SBIR follow-ons of that size are still pretty rare, all things considered. STTRs are just SBIRs with a university or non-profit partner that takes 1/3 or more of the money.

There were ~6500 SBIRs awarded in 2022. Historically the top 5% of the companies receive 49% of those funds and the top 25 of those companies (.5% of contractors) received 18% of the funds deployed in SBIR Phase I/IIs. Of those top 25, just 4 actually managed to transition their tech to Phase III (16%). There are companies called SBIR mills which basically just do SBIR contracts all day for the meager 10-15% fee you can book off a government research contract, but those aren’t venture backable. Bottom line: Phase IIIs are pretty rare with only a couple dozen awarded each year and the odds your company will make it that far are slim. Best not to hang your hat on them as your path to PoR.

It’s important to realize that SBIRs are more of a grant you might make a little money off and allow you to do internal BD in the government, then a viable business model.

Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs) are a special streamlined contract mechanism design to allow more rapid acquisition. OTAs are typically awarded through consortia that require an application process and membership dues for management. They can be quite a bit larger (I’ve seen billion dollar OTAs before), but are usually more one time shortcuts for an interested customer than a permanent program of record. In fact, if you read the OTA criteria for selection they are specifically intended for prototyping, with some wiggle room for production follow on. The contracts must include significant Non-traditional defense contractors (NDC) contract, meaning they haven’t been awarded a Program of Record before or are not subject to federal Cost Accounting Standards (CAS) for any contract in the past year - meaning no Cost Plus or Fixed Price Incentive contracts in their recent history (CAS compliant contractors can get around this by including a cost share component of 1/3 or more in the contract). This last part is crucial: this is not a play you can run every time - eventually you are going to get contracts large enough to knock you out of the NDC category. Some companies like SpaceX can get around this by refusing to ever do CAS compliant contracts but that’s not something everyone can do.

IDIQ (Indefinite Duration Indefinite Quantity) contracts sometimes can be used for programs of record as well (the services buy a lot of infrastructure like bunks, laptops and other things through IDIQs). The key thing to understand with an IDIQ is that the top line number is often very high (I’ve seen IDIQs in the billions) but that is really just a credit limit - it’s not what the IDIQ is actually funded for. It’s extremely important to understand exactly how much money is really budgeted in the IDIQ and a lot of them are basically just structured as catch-baskets with the hope they can opportunistically transfer/MIPR money in later.

Further complicating things, it’s usually a two step process to get awarded an IDIQ, with the first RFP being to identify eligible participants. If you are let in to the IDIQ, you will then need to bid on individual task orders, some of which may be competitive with other contractors. So while IDIQ awards are cool, they are by no means dependable income, unless they are sole source and fully funded (which is rarely the case).

Big picture: approximately right vs precisely wrong

Larger more mature companies like Boeing and Raytheon go so far on “must win” proposals as to “buy-in” early in the development process, ie - intentionally bidding early development business for a loss- to win the larger, longer and more lucrative production contracts - many of which lack the traditional “Cost-plus” margin caps of 10-16% that would make their stock less attractive. Their track record using this approach is mixed (e.g. KC-46 tanker) but given that these companies are over 100 years old and still large players in defense, this must work at least some of the time. This is also the exact same game that VCs play when they Blitzscale to achieve dominance in a particular market, only here its guaranteed if you win as opposed to much more of a crap shoot with blitzscaling.

When it comes to market estimates for defense, its important to not get hung up on exact amounts - its highly likely given the uncertainty of federal defense budgeting, shifting priorities and other factors that actual yearly revenue may fluctuate somewhat. Remember Warren Buffett’s adage on estimates:

“I’d rather be approximately right than precisely wrong”- Warren Buffett

You should really focus on having a solid understanding of what the potential real product revenue is for the company and not get distracted by chasing CRAD like SBIRs, OTAs and other mechanisms that aren’t explicitly linked to your product development and Go To Market strategy. These contracts are great pointers to early progress and can help keep the lights on, but will not fund the product forever and you’ll never get rich at 10% margins on what are basically service contracts. Real market size analysis should focus on product revenue in sticky and growing Programs of Record that will always remain the holy grail of defense funding and should be the GTM aim point of any defense start up.

fantastic analysis

Great article, but the OTA section is factually incorrect.