"It Worked in Ukraine" Is Not a Substitute for Rigorous Test & Evaluation

The urgent need for real world EW testing of drones in the US

US drone acquisition about to enter hyperdrive

This past week, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth publicly signed (with Metallica background music) a directive “taking the department’s bureaucratic gloves off” of US military drone production and fielding.

The directive, entitled “Unleashing US Military Drone Dominance” comes weeks after President Trump’s June executive order to streamline and modernize our nation’s drone laws, “Unleashing American Drone Dominance” (that’s two levels of unleashing). The Hegseth directive outlines several policy changes and directives to occur in the next 30-90 days:

Arming combat units with a variety of low-cost drones

More widely integrating UAS into training exercises by 2027

Each service will create program offices focused on UAS, especially small UAS.

DCMA is going to assume a role in Blue UAS with joint management from DIU.

Identify programs that could be cheaper or more lethal if replaced by drones.

Form experimental formations purpose-built to enable rapid scaling of small UAS across the Joint Force by 2026, w/ INDOPACOM taking first priority

Designate at least three national ranges, with diverse terrain (at least one with over-water areas) for deep UAS training, w/ low/no inter-service cost transfer.

All of this is absolutely wonderful and long overdue. It’s about damn time we started to try and catch up with our adversaries like China, which just placed an order for 1 million kamikaze drones to be delivered in 2026.

But it’s also important that in the interest of speed we don’t rush headfirst from one problem into another: the simple reality is that most American drones have not been rigorously tested to work in the dense electronic warfare environment of Ukraine nor recent Middle East conflicts. Worse than that, we lack doctrine, equipment, ranges and procedures to even test them thoroughly in the presence of dense jamming and interference.

The struggle is real when our systems come into contact with the EM hellscape in Ukraine. Many first generation drones outright failed to even take off due to interference and jamming. Most have difficulties with interference from similar drones used in close proximity on the same frequencies - a phenomena known as RF fratricide. Modular payloads and warheads frequently can suffer from cosite interference (different radios interfering on the same platform), conductive susceptibility (bus emissions compatibility/instrument noise) and perhaps even HERO (spontaneously blowing up due to RF interference) issues.

Part of this is that we built many of America’s drones backwards: because we started development in permissive environments, we didn’t build in features for operating in an EW environment from day one. Even worse, once we figured this out, it was hard to find places to test UAS and Counter UAS systems in the US - due to FAA and FCC restrictions on airspace and spectrum use - and as such, testing is infrequent and we currently lack uniform procedures for how to properly test drones. As one test lead for the Navy’s only test & evaluation squadron for drones, UX-24, confirmed for me last week “there is no department wide memo on uniform UAS and counter UAS testing”.

As drones rapidly come into widespread use we must take steps to develop uniform procedures to rigorously model, simulate, test and evaluate these systems to develop a deep understanding their capabilities and limitations in the complex electronic environment of electronic warfare - drawing inspiration for what we do for radar sensing and jamming systems on aircraft with appropriate tailoring.

If you don’t think the Taiwan strait will be an EM Spectrum Operations Hellscape even worse than Ukraine, I’ve got a bridge in the Jiangsu province I’d like to sell you. Our drones must be prepared to survive and thrive in this environment - or else we are just building lots of cheap cannon fodder for our adversaries. We prove this through rigorous modeling & simulation, testing and evaluation. Building drones and systems that can survive and thrive in the EM battlefield of today and tomorrow is the raison d’etre for CX2 and a lifetime passion project for yours truly.

Potemkin Combat Validation

To their credit, many sUAS manufacturers from US and Europe recognized Ukraine as a proving ground and have been willing to iterate through failures on the battlefield to prove their upgraded systems work there. However, this leads us into our second problem: “combat validation” without rigor to prove something works across the range of military operations isn’t combat validation at all.

“It worked in Ukraine” has turned into almost cliche. Pilot deployment in a combat theater is necessary but not sufficient for wide scale deployment.

The Ukrainians have been getting smarter about Westerners just showing up to “check the box” on combat validation. “…They (Western firms) do beautiful pitch books, beautiful presentations about how they’re operating in Ukraine. But actually they’ve done just a couple of flights in Lviv [the western city more than 1,000km from the front line]…The big problem, after that, is that billions of dollars go to the companies that still don’t have any idea what they’re doing.” said Roman Knyazhenko, CEO of Ukrainian drone firm Skyeton in a particularly damning piece in the past week’s Telegraph. This is a recurrent theme with Ukrainians we talk to: western defense co’s showing up to do the testing equivalent of seagull management and then bugging out after fairly benign testing to “check the box” of combat validation for marketing purposes- that’s why the Ukrainians are so cynical about western UAS and CUAS systems.

Rigorous systems engineering is necessary to prove that combat validation wasn’t just a result of cherry picking conditions under which you flew in theater so that your drone would be guaranteed success. Without running a system through full test, simulation and evaluation conditions, purely empirical results and phony validation like “It worked in Ukraine” tells you nothing about how something will work throughout the full range of military operations, from moderate RFI to massive jamming and interference. Even the Ukrainians, who have been building and flying in this environment lose over half their drones to jamming and accidents, driving them to tethered drones to take out high value targets.

During my time in Ukraine, I collected statistics on the success of our drone operations. I found that 43 percent of our sorties resulted in a hit on the intended target in the sense that the drone was able to successfully fly all the way to the target, identify it correctly, hit it, and the drone’s explosive charge detonated as it was supposed to. - Jakub JacJay, “I Fought in Ukraine and Here’s Why FPV Drones Kind of Suck”

For combat validation to be meaningful, it must occur under conditions that are understood to be rigorous and there has to be some degree of data collected can be at least somewhat recreated in simulation and test, ideally by a third disinterested party. The long term benefit: those same tests and simulations can be used to test new systems and improvements building confidence in performance without having to roll the dice again and hoping it works in combat.

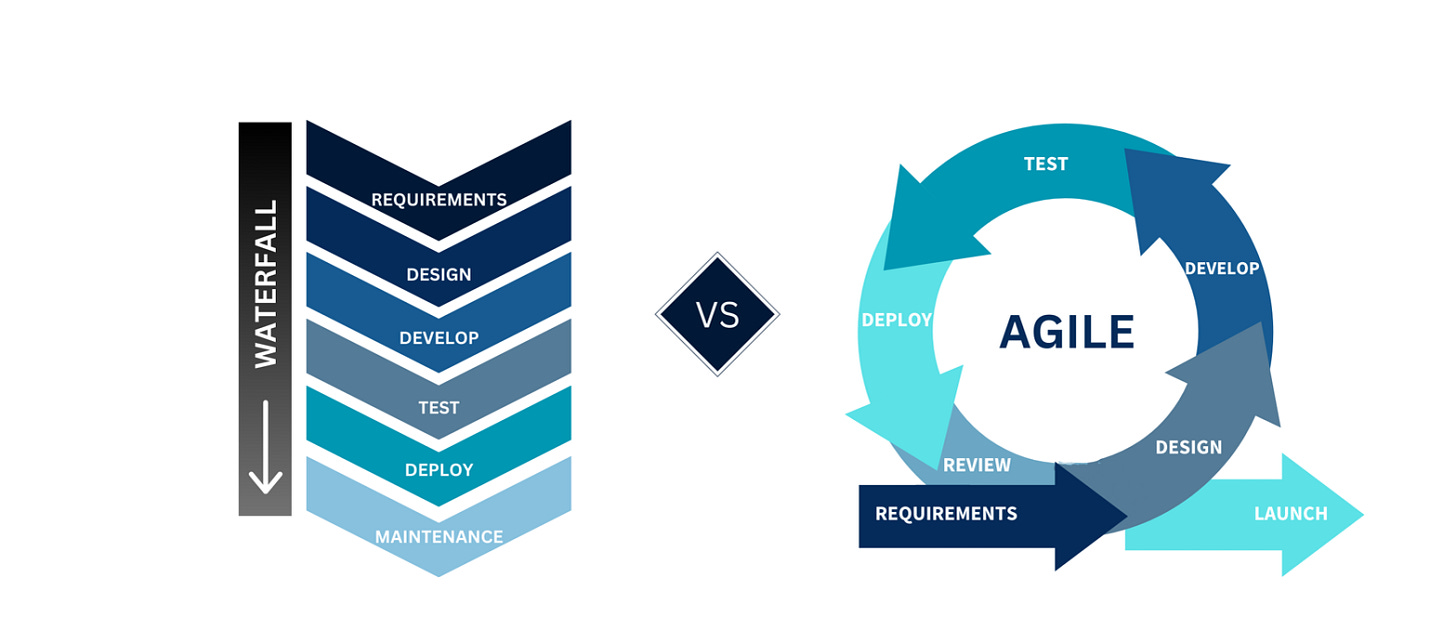

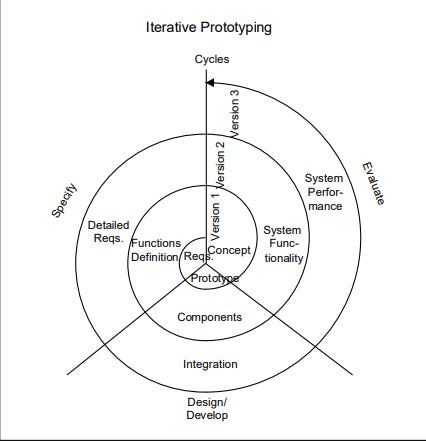

Iterative prototyping vs. Agile vs. Waterfall

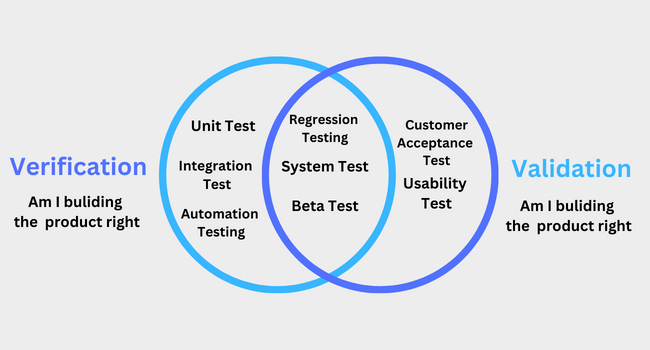

In venture backed start ups (especially software ones), there is a race against time to get a product into pilot with a real customer and generate feedback based on their experience. This is an essential part of the agile development process (shown below). Compare and contrast this with the linear waterfall process which traditionally is used for hardware development (see below).

This is perhaps a key gap worth highlighting between the agile approach and the waterfall approach to development: while agile development embraces piloting systems with real world customers as quickly as possible to receive feedback, it can sometimes lack the verification a product works over a wide range of conditions before widespread deployment. For consumer products, it’s ok to let the customer be your guinea pig and do some of your defect discovery (to a point); for systems people’s lives are depending on, not so much. The desperation of the wartime situation in Ukraine has forced a lot of UAS product teams to have a higher tolerance for defects out of necessity, but that is by no means ideal. The reality is that combat validation without verification leaves us with major gaps in our understanding of system capabilities and limitations we may fill in later the hard way. With each design iteration adding more, the level of fidelity in our testing and simulation must increase as well, particularly if the product is in widespread use.

Verification vs. Validation

The traditional waterfall approach to weapons and system development from the DoD is way too slow for the current era of consumer scale warfare and agile development/iterative prototyping is necessary to keep up with a rapidly evolving enemy. However, historical DoD testing systems such as the IDAL Research Program at AFRL or the Weapons Systems Evaluation Program can potentially serve as a roadmap for how we can design a rigorous test framework that enables validation results to feedback into the verification process and build confidence that we are building the right thing. These studies also serve another key function: providing real world validated estimates of essentials like Reduction in Lethality (RIL for jammers), Probability of Kill (Pk for missiles) and exchange ratios (for fighter aircraft) which can be used in force planning and budgets. We have to find a happy medium between the need to move quickly and avoid non-value added paperwork exercises and the need to be able to determine and predict system effectiveness without putting real lives at risk.

We have to find a happy medium between the need to move quickly and avoid non-value added paperwork exercises and the need to be able to determine and predict system effectiveness without putting real lives at risk.

A key cornerstone of good iterative prototyping is to develop a full suite of simulation and testing systems that you can rapidly implement a systematic verification procedure on every time you make a change and determine results before you fly. SpaceX makes this a cornerstone of everything they do and it shows in their unprecedently high reliability for launch. Tools like hardware in the loop (HITL) and software in the loop (SITL) simulators and flight test ranges filled with jammers using containerized and characterized techniques for jamming to test against enable systems to be verified and validation runs checking against results observed in a wartime environment. Add to this the accessibility of new enterprise software tools like Sift, Epsilon3 and others, which give an engineer unprecedented observability into how a system is functioning, and these processes can be done orders of magnitude faster than they have in the past.

Bringing the drone down for landing

“It worked in Ukraine” should be necessary, but not sufficient for drones arming US forces. We have spent decades developing a robust modeling & simulation, testing & evaluation and verification & validation framework for missiles, radar EP and radar jamming, as well as for communication systems and other sensors. We have factor spaces, detailed threat laydowns and a long history of FME/FMA (foreign military exploitation and analysis) to determine exactly how effective enemy sensors and jammers are so that we can allocate funding to address different technologies to help solve the problem and also so that we can build robust Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) to defeat them.

We need to use a framework like the Weapon Systems Evaluation Program (WSEP) we use for missiles as inspiration and create a new verification and validation process for the “attritable” weapons category that drones fall in - firmly rooted in ensuring they can operate in an EW dense environment. Perhaps a full blow T&E gauntlet doesn’t make sense for $1500-$50k drones, but a modicum of this level of systems engineering rigor could go a long way towards supporting accurate force planning and ensuring our troops understand the capabilities and limitations of our own systems. The ease of set up and use of SITL, HITL and simulation tools should make this relatively easy and inexpensive for the services to set up in collaboration with industry.

CX2 will continue to be at the forefront of this, both building systems to survive and thrive in the EW dense environment of the 21st century battlefield and the software and hardware tooling to prove they do while iterating rapidly. We will also continue to advocate for the services to receive and or develop the resources, ranges and procedures to help industry do this and provide independent verification and validation. Nothing short of our warfighters lives depend on it. We need rigorous EW testing for our drones - and fast.