A new approach to developing and buying counter drone systems

Unifying Counter UAS capabilities across the DoD moves forward with new found urgency

Finally Putting Authority, Money and Expertise Under On Roof

Last week, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth released a memo “Establishment of Joint Interagency Task Force 401” which sought to fix a gap in how Counter UAS systems are tested, evaluated and procured across the DoD.

Reporting directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the new task force is authorized to field tech rapidly, tap $50 million per effort without delay, and hire specialized staff from S&T labs plus counter-UAS experts across the services. Replicator 2 is absorbed into the new unit, and the Army and Pentagon partners get just one month to carve out a secure workspace and prepare FY 26 budget requests. This isn't just a reshuffle—it’s a hard pivot toward speed, agency, and unified action in the face of an accelerating threat.

The memo took aim at a long standing problem: the organization within the Army which is the central touch point for CUAS across the DoD, the Joint Counter small UAS office (JCO), at present has a lot of authority to test and evaluate CUAS systems but lacks sufficient budget authority to contract outside vendors to develop and procure them. All they can do is test & evaluate and slap a label of “JCO approved” on solutions, while relying on other organizations like the Army Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies office (RCCTO) to use OTA and other contract vehicles to acquire and maintain these systems. This is somewhat emblematic of the “authorization vs appropriation” split that exists all over the DoD (you need both to proceed with something but the two come from different sources) which slows down roll out of new systems and leads to lots of internecine fighting over budgets and authorities.

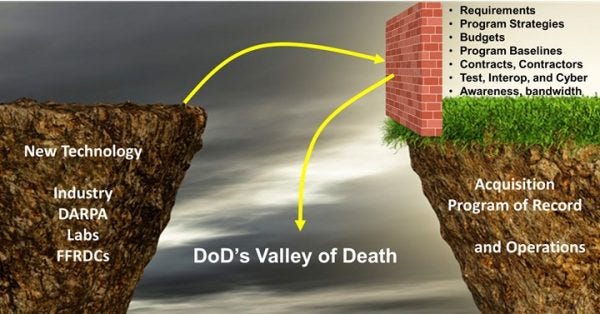

This split has led to hundreds of potential CUAS solutions languishing on the wrong side of the “acquisition valley of death” with customers/warfighters saying they want their solutions but lacking the means to procure them. Meanwhile, our adversaries are literally buying drones by the millions while we are barely outfitting our front line units with Counter UAS systems capable of defeating them.

“The small UAS threat continues to grow exponentially and is becoming increasingly sophisticated. The number of DoD organizations involved in C-sUAS since…2020 has increased, and those organizations often are unconnected to each another. DoD needs a single focal point to centralize, coordinate, and lead these efforts.” - memo establishing JIATF 401

How did we get here?

For years, C‑UAS felt like the red‑headed stepchild of DoD acquisitions—a critical but under‑loved mission that splintered across stovepipes. Counter‑UAS work traces a lineage from JIEDDO (born from Joint Counter‑IED efforts in the mid‑2000s) now evolved into JIDO, which later took on small UAS threats. The real structural pivot came in 2020, when the Secretary of the Army—acting as DoD’s Counter‑Small UAS Executive Agent—stood up the Joint Counter‑Small UAS Office (JCO) under Army G‑3/5/7, partnering with RCCTO. JCO was meant to streamline doctrine, requirements, materiel, and training—but lacked procurement authority, largely sticking to test and evaluation, fielding demos, and endorsing vendor systems without the capital to pick up the tab. That fueled a chaotic landscape of vendor solutions and too‑many fledgling C‑UAS firms stranded in the acquisition valley of death.

The establishment of JIATF 401 today signals a tacit admission that evaluation and acquisition can’t live in silos. JIATF 401 is created to report directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense, armed with rapid acquisition authority, hiring flexibilities, and consolidated funding that could push counter‑drone tools out into the field at speed the threat. The message couldn’t be clearer: if we want scalable, deployable C-UAS at warfighter speed, you assemble capability, authority, and resources under one command. That’s the hard lesson—and hard pivot—this reorg embodies.

A couple other key details behind this effort: existing service specific CUAS projects, such as IFPC-HPM (which encompasses Epirus’s Leonidas Block II), Army M-LIDS or X-MADIS are likely not included under this, since they have existing program offices. So called SOF peculiar procurement is also exempt so Special Operations Command still has flexibility to move quickly within its own mission scope. But all new RDT&E efforts go under JIATF 401.

Testing limitations are a pacing item for new development

While it’s great to see this effort getting started and real money getting put behind rapidly solving one of our most urgent capability gaps, JIATF 401 still has more work to do. While the memorandum calls for identifying and creating dedicated C-sUAS testing ranges in a months time, the spectrum authorizations for actually operating jammers and wider bandwidth radios on these ranges will also need to be addressed.

At present, there are few, if any places in CONUS where CUAS and GPS jamming can occur persistently. Anyone using a GPS jammer in the lower 48 for longer than 15 minutes at present can expect an angry call from the FAA due to the perceived need for pristine spectrum access for civilian use due to our highly congested and dynamic airspace. This may require NDAA language and reforms to the FAA charter through legislation in order to fully fix.

Even the most ambitious ranges and exercises can run into economic and geographic limits so it’s important that we don’t ignore modeling & simulation development either. Efforts like AFRL’s Digital RF Battlespace emulator program should be expanded to allow us to evaluate the efficacy of effectors and detectors in large one v many autonomous system scenarios such as swarm on swarm operations.

Expanding industry access to test ranges

We also need to make it easier for industry partners to access CUAS ranges on a regular cadence without being paced by the DoD. One of the things I was most surprised by when I went to Ukraine was how quickly CUAS manufacturers were able to get onto government test ranges and immediately evaluate low TRL tech - from the outside its very tightly integrated, yet informal and almost effortless.

Contrast this with US ranges which can take many months to coordinate and get the authorities and sponsorships to operate on. Exercises such as TREX, Silent Swarm and others can often times take nine months or more of planning to get a low TRL product on a range to test. Juxtapose this with the one month procurement OODA loop in Ukraine and you can see there is a gap here. The reason its possible is because their approach is much more relationship (“Yuri has a reason to be here and the range is open”) than process focused (“please fill out these 25 forms and talk to the central planning authority at the flag pole - they’ll get back to you in six weeks”) and we should take notes.

Perhaps the closest analog we have to the Ukrainian model is CRADAs. We need more meaningful CRADAs (Contractor Research & Development Agreements) in place so upstarts, startups and established players - with the attention and resources behind them - that can access the CUAS range for continuous experimentation without the availability or attention of an overstretched government POC being the pacing item.

Leveraging the full western enterprise

DoD is also not the only part of the US government buying Counter UAS systems. Homeland Security is also looking at their own $100M CUAS acquisition program with multiple buys through an IDIQ. How tightly integrated will this be with DoD’s JIATF 401? There are many similarities for DHS mission vs DoD (My spidey sense is there is about 85-90% commonality amongst requirements), but some differences. DHS has a larger focus on apprehending the subject rather than destroying the drone (shoot the archer, not the arrow) and is more gun shy about collateral damage due to operating over the homeland - which may make them favor more reversible/electronic attack vs kinetic effects. Nonetheless, DHS should be able to heavily leverage JIATF 401 resources to drive economies of scale and mature promising tech faster.

Finally - we need better integration with our allies across NATO, Ukraine and our partners in the Indo-Pacific like Australia, Japan and Korea to fully leverage all their lessons learned, learn how to integrate with disparate and diverse systems as a fighting force and increase the economies of scale of the industrial base.

CX2 just returned from the Pacific Futures Forum in Tokyo this past week and one of the consistent themes across all the panels from our allies was tighter systems integration across forces. Japanese Self Defense Forces (JSDF), Norwegian and UK ships are operating in formations together and even going as far as to integrate individual air platforms on to each other’s ships for the first time so that they can operate more seamlessly as a single fighting force. Our drone forces across the allied fleets are even further away from this reality. With the Chinese building 70-80% of global drone production a year and adding the equivalent of the entire Royal Navy to their own Navy every year, our ability to integrate UAS and CUAS systems across all allied nations will be even more critical to staying in the fight longer through greater depth in future near peer conflicts.

* *

So to summarize: JIATF 401 is a huge step in the right direction, but more work remains to be done to ensure that we convert this new found urgency and consolidated decision making into lethality.