Love Me, Tender: Drone Edition

How One v Many is driving systems for automated care and feeding of unmanned autonomous systems

Going from 1 v 1 to 1 v many

Readers who tuned in for my last post will recall a list of critical technologies and products that I outlined that must be developed, matured and deployed for us to move from First Person View (1 v 1) to Real Time Strategy (1 v many) on the battlefield and beyond. Despite what the science fictions authors may have you believe, autonomous drone swarms still are a very nascent technology.

The list (which I by no means claim to be exhaustive) is rehashed below:

Real time command & control at scale

Control Abstraction Layer (going from high level commands to complex maneuvers)

Intra-drone communication and coordination

Robust local precision navigation and timing (independent of GPS at least intermittently)

Tendering: how are these drones deployed, recharged and resupplied at scale

Last week I covered #1 and touched on #2. This week I’ll be diving into #5: all things tendering since this is an area with quite a bit of activity and upstarts and mature players alike are trying to answer the question: how do we deploy and maintain all these drones? For folks that are still trying to figure out how to make autonomy work at even a 1v1 scale, tendering may seem a long way off, but figuring out the physical infrastructure is a huge part of how we deploy at scale. We may be a ways off from the Protoss Carriers from Starcraft shown in the video below, but there are plenty of impressive intermediate systems to share.

Amateurs study tactics, professionals study logistics - Napoleon

Drone docks

We have docking stations for Roombas, for our phones and laptops. Why not for drones? Major drone manufacturers in the US and China have started to roll out “drone in a box” solutions for commercial and security drones. These provide drone storage, drone charging and command and control in an easily deployable system with a retractable dock. Skydio has it’s drone dock product, Emergency Responder Drone company Brinc has it’s responder station and of course DJI has their own dock product as well. These are all singular instantiations (i.e. one drone per dock) but could easily be mounted on roof tops or as DJI’s promotional video shows, readily transported in the back of a truck (conceivably the others are capable of this as well.

The prize for best drone dock marketing however, goes to A2Z Drone Delivery, that made this almost Hollywood quality video showing their vision for drone docking and deployment at scale (pretty remarkable for a bootstrapped company). Others like Zipline, Volansi (acquired by Sierra Nevada) and several others are also in the space and will be deploying their products commercially at scale in the next couple of years.

For drones to actually be deployed at scale for logistics or commercial delivery, docks like A2Zs will need to become as ubiquitous as Amazon fulfillment centers or intermodal trucking hubs.

Aerial Drone Carriers

Speaking of Amazon, they made waves back in 2016 when they were awarded a patent for a “airborne fulfillment center utilizing unmanned aerial vehicles for item delivery”. My understanding (from talking to people hired to continue working on this) is that Amazon is continuing a low level of work on the concept, but filed the patent defensively so that no one else could jump on the claim while they waited for the technology to mature further.

This concept is in some ways over 100 years old: in the early 1930s the US Navy experimented with a pair of blimp aircraft carriers - the USS Akron and the USS Macon. Both airships were lost in storms, with the only evidence of their existence being the massive hangars at Moffett Field (in Mountain View) and a few other places throughout the coast.

The Ukrainians, driven by pure necessity have built and deployed their own drone carrier drone of their own: the Dovbush. This drone is capable of carrying up to four kamikaze drones, which it can command via either radio or a shorter range fiber optic tether. The video below shows this system in action. Launching from a mothership brings with it the advantage of more robustness to jamming and being able to leverage more exquisite systems for navigation, data links and longer range versus what the smaller drone can do on it’s own.

The Chinese have a Group IV (Predator sized) drone called the Jiu Tian, which includes an “Isomeric Hive Module” suspected of being a drone tendering unit. This would give the Chinese the ability to deploy drone swarms well beyond the FLOT (Forward Line of Own Troops).

The US military meanwhile has focused its attention on programs such as Enterprise Test Vehicle (ETV), also known as the Rusty Dagger program. While mostly focused on deploying missiles with a 500NM+ range at scale, the Rusty Dagger is intended to launched from the back of a C-130s or similar cargo aircraft, perhaps as many as dozens at a time. This is a natural outgrowth of the DARPA Gremlins program from about a decade or so ago which showed the potential for launching a small air force from the back of a C-130 and then recovering the drones if desired.

Anduril’s Barracuda missile program and Zone 5’s Rusty Dagger were both downselected earlier this year for the next phase of this fly off. With the defense innovation money pumps potentially being cranked wide open with the new budget, it will be interesting to see where this lands.

Mobile land based drone carriers

Land based carriers are also starting to be fielded at scale on the battlefield. Since about 2016, the Chinese have fielded a drone carrier truck capable of launching and controlling up to 48 of its CH-901 attack drones, as shown in the video below.

The Russians have also fielded several drone trucks of their own. Surfacing in the Kursk offensive last year the Kub-SM by Kalashnikov includes tendering and command and control capability for up to 16 drones (2 recon drones and 14 attack drones). Kalashnikov boasts that it can also launch fiber optic drones, which would be timely given their current popularity due to the ubiquitous jamming environment seen in heavy fighting in Kursk and Kharkiv in the last 12 months.

The Kub-SM joins the Multi-Launch Drone System (MLDS) on the battlefield, which carries up to 16 tube launched versions of the popular Lancet kamikaze drone.

It’s highly likely that both of these Russian systems were inspired by the Iranian Shahed-136 deployment truck, which has become a mainstay of military parades in Iran. The Russians have become the beneficiary of a great deal of drone tech transfer from Iran, including setting up large scale production of Shaheds in Russia.

Perhaps the most famous and oldest example of a drone delivery truck is the ground system for Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI) Harpy drone. First fielded in 1989, the Harpy was in many respects the first loitering munition and came equipped with an anti radiation homing seeker. The Harpy is often deployed in a truck mounted magazine of up to 10 missiles, as shown in the figure below:

Most of the innovation in the US market has been for commercial use, with relatively few military entrants into the military drone tender truck market (so far). A few US companies are actively marketing Drone tendering systems that can be mounted on trucks. One outfit called Accelerated Media Technologies is marketing a “Mobile Tactical Drone Operations” truck capable of launching a single tethered drone from a shelter on the roof.

In 2018, a US firm, Workhorse Aero, a subsidiary of Workhorse Trucks (make EV delivery vans), was awarded a patent for a drone delivery system from a truck they called Horsefly. This may have been a case of being too early to market, as Workhorse Aero has since pivoted out of the drone manufacturing business.

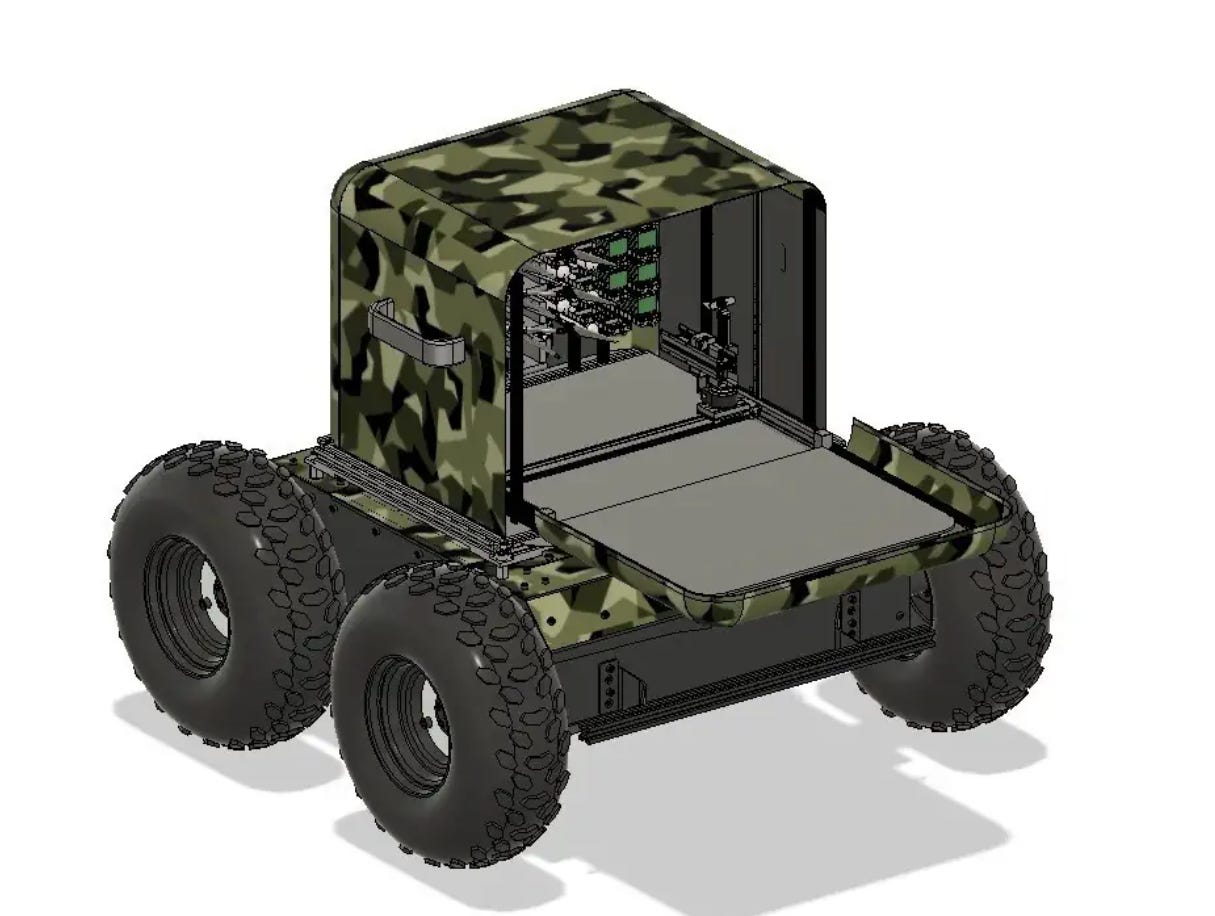

The only military focused firm I’ve been able to uncover so far is Airrow, a small firm in the San Fernando Valley which recently won an Air Force Phase I SBIR to deploy a drone tendering system on an unmanned ground vehicle. This is basically a ground version of the Ukrainian Dovbush, with two degrees of UAS supporting each other.

Drone Carrier Ships

While US Supercarriers are slowly adding Drones to their air wings, like the MQ-25 Stingray which is meant primarily as a refueling platform, the rest of the world is busy building specialized ships for fielding drones at scale. Most US drone carrier efforts have been focused on folding into the existing NavAir concept for the manned air wing. Other countries without a long history of carrier aviation have been busy looking at alternatives, however.

The English went so far as to commission a study of the feasibility of the drone carrier concept almost 20 years ago with BAE Systems working on the so-called the UXV Combatant program. This was eventually shelved in favor of just folding in UCAVs and other drones into the existing carrier air wings on the two Queen Elizabeth Class Carriers they presently operate.

The Turks recently launched the TCG Anadolu, a ship which can carry anywhere from 30 to 50 drones, including the Bayraktar TB3, a drone designed for carrier launch and recovery and the more advanced Bayraktar Kızılelma, a purportedly low observable (stealth) jet powered UCAV (unmanned combat aerial vehicle). The fact that Turkey was the first is likely due to its exclusion from the F-35 program which forced them to develop alternatives. Also the Bayraktar drones built by Baykar have seen heavy combat action in both Ukraine as well as Azerbaijan, giving them significant lessons learned to fold back into these systems.

The Iranians recently launched their own drone carrier, the Shahid Bagheri. Refitted into a drone carrier from it’s start of life as a cargo carrier, the Shahid is purported to carry drones that are smaller versions (60 or 25% scale) of it’s jet drone projects. Equipped with a launch ramp like most non CATOBAR (catapult launch) carriers, it’s highly likely that this project the same sort of prestige act/vaniety project that Iran is notorious for, with extremely limited military utility.

Finally, the Chinese have gotten quite a bit of attention from the launch of it’s Type 076 Amphibious Assault Ship, the Sichuan. This drone ship is massive - as large as an America-Class Light Helicopter Carrier - 50,000 tonnes and 800+ feet long. Little is publicly known about the system though it’s purported to have a “drone first” airwing and electromagnetic catapults capable of operating larger (Group III or IV) UCAVs. It’s highly likely that this first of it’s class ship will serve as a test bed for drone carrier operations and tactics for an all drone air wing. I hope we’re taking notes. Great video below if you have 15 minutes:

Bringing it all together - drones all the way down

As drones become more and more ubiquitous, the logistical challenges of launching, recovering and tendering them at scale will be as big of an issue as any. In particular, the desire to make other unmanned platforms as launch platforms for aerial drones will give us a bit of a “turtles all the way down” feel to 21st century warfare. Imagine an autonomous ship launching smaller autonomous boats, carrying unmanned ground vehicles with drone launch systems of their own? Kind of reminds you of this classic meme a bit, doesn’t it?

Entirely new lines of logistics will have to be considered to carry the energy capacity to charge or refuel all these unmanned systems, repair them if possible and ensure their software is up to date. The tendering is only one (significant) part of the challenge however: command and control at scale and intra-drone communications also need to be solved for and will be the topic of my next entry.